Smell is the most neglected of our senses. The standard cliche observation to support this is that we don’t even have that many words for describing how things smell.1 Nearly all of the words we use are borrowed from other senses: taste—something can smell “sweet” or “zesty”; touch—we can describe a smell as “sharp” or “soft”; sound—we talk of “loud” perfume or “high-pitched” notes; even the convention of describing the components of a scent as notes is borrowed from music. Describing smell can also rely on recursion—a pineapple smells, well, like a pineapple. It’s generally agreed that smell is at the bottom of the sensory hierarchy, which is why we need to make a conscious effort to cultivate an appreciation of this neglected sense if we want to fully incorporate it into our sensory and aesthetic experiences.

There’s already plenty of good information out there about how to get into fragrance as a hobby and enjoying perfume as a beginner that I don’t want to repeat. My goal here is to share some fundamental advice that anyone can follow to start appreciating their sense of smell more fully.

I want to note that all of the advice herein does not require you to buy anything. Though I am an avid perfume collector I also firmly believe that you can love and appreciate fragrance without amassing a collection. A lot of the aforementioned advice includes tips about what to buy and how, which, again, I don’t think needs to be repeated.

Start paying attention to how things smell

It’s literally that easy. You can stop reading now. Just go out there and smell everything.

When you’re out in the world take a second to observe the smells around you. You’d probably notice if you walked by a bakery that was pumping out delicious morning pastries, right? You might even stop for a minute to enjoy it. Start treating every moment as an opportunity to engage your sense of smell. How does the air smell while you’re walking through a local park? Go back to the same spot on a later day and notice how it smells different from your previous visit. Think about how the air changes throughout the seasons: what smells are dominant in fall versus winter? Spring versus summer? Everyone’s house smells different. How does your best friend’s house smell? How does your mom’s house smell?

A sub point of this principle that I want to emphasize is:

Don’t Shy Away From Any Opportunity to Cultivate Your Olfactive Prowess

No matter how disagreeable, even bad smells can be an opportunity to exercise your olfactive powers. Walking by some particularly gross garbage? How would you describe it? How does it smell different from the garbage down the street?

I live in New York City—the land of freely-strewn garbage—so this is the easiest example to draw on from my personal experience, but if you live elsewhere you surely have scenarios particular to your locale: maybe you live in the land of traffic jams or abundant horse shit or in close proximity to a paper mill. Any stink-portunity is fair game.

Once, I was trapped on the subway sitting next to a guy who smelled absolutely awful. Rather than shy away from him, or resign myself to passively stewing in his stink, seething and wishing I was elsewhere, I faced the situation head on and used it as an exercise in describing smell:

I guess this is, like, a mindfulness cultivation kind of thing, which is kind of corny, but it works. Wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, it’s an opportunity to exercise your nose.

Get to know the smells around you

The easiest way to do this is to dive into your kitchen spice cabinet. Sniff all your herbs and spices. Which ones seem similar? If you’re having trouble describing any of them beyond “spicy”, pick up a few and compare them to each other. Try cardamom, coriander, and cinnamon. Perfumers categorize spice smells as “warm” or “fresh”. Which spices would you describe as warm? Which ones would you say are fresh? Which have aspects of both categories? Comparisons can be one of the best ways to learn different facets of a fragrance. How does red pepper smell compared to black pepper? How does fresh basil smell compared to dried basil? Vanilla is one of the trendiest notes in commercial perfumery right now. If you have a bottle of vanilla extract give it a sniff so you understand what it smells like. Even better, if you have real vanilla extract and artificial vanilla extract, compare them to each other. Which one is sweeter? Which one smells more “perfume-y”?

Give other things in your kitchen a sniff. Tea can have a particularly complex scent all on its own—how would you describe it? If you have a bag of Earl Grey you can learn to recognize the smell of bergamot, a type of citrus fruit that is very commonly used in perfumery.

Arabelle Sicardi wrote up a nice post with similar advice, using citrus as an example. Even with a simple orange you have several opportunities to cultivate your sense of smell. Cut the orange open. Peel off a bit of the rind. How does the peel smell compared to the flesh of the fruit? Which is sweeter? Which parts would you describe as “sharp” or “tart” or “bitter”?

Move beyond the kitchen. Give any wood furniture you have a sniff. Smell your leather jacket. Smell things in your environment that you wouldn’t consider particularly fragrant.

In addition to collecting perfume, I also collect taxidermy. I have a taxidermy flamingo that is one of the highlights of my menagerie. It also happens to smell fabulous and I dream of having a perfumer recreate its scent. The flamingo smells like: wood wool (dry wood, a little cedar-y, like a pencil), dust, and something clean but a little animalic, a bit like cat fur. Sniff all the things in your house you’d never think to smell.

Find your oldest book. Fan its pages open and inhale. “Old book smell” is often cited as a favorite fragrance. What does it smell like? A bit dusty and woody, perhaps. Maybe a bit tannic like the tea in your cupboard. Depending on how old the book is it might even smell a little bit like vanilla. Vanillin is an aroma molecule present in natural vanilla that can be synthesized from the lignins in wood pulp for use in perfumery and flavoring.

Write down your observations about the fragrances around you, or record them as voice notes. Keep track of what you like and don’t like. Think about why you like or don’t like particular smells.

Which brings me to my next point:

Think About How to Describe Smells

Professional perfumers and other people working in the fragrance industry have a shared vocabulary that they work from when describing fragrances. For the first year or so of perfume school students basically just smell things and describe them. There are classes where you can get an overview of how to talk about fragrance using this framework. Or if you want to explore it on your own there are resources that can guide you.

A shared vocabulary is required for the categorical precision that is necessary to produce a commercial fragrance, or to understand and contextualize the historic evolution of perfumery over time, but you don’t have to limit yourself to describing fragrance using this vocabulary. It can be helpful if you want to approach fragrance academically, but it can also be rather limiting when it comes to expression.

Maybe you are completely uninterested in describing fragrance with words; you just want to experience it—that’s totally understandable (even a bit admirable), in which case you can feel free to skip this section.

A lot of fragrance writing/“content” is really just a regurgitation of the notes that a marketer delineates for a given perfume, as though “X smells like A,B,C” is the endpoint of critical analysis for fragrance. This is boring and exemplifies the cultural moment we live in where an unambiguous explanation of any particular work of art is considered a requirement to appreciating it—if art cannot be fully exculpated it is considered “bad” (see for example: the thousands Youtube explainer videos entitled “[NAME OF FILM] Ending Explained” as further evidence of this phenomenon). I want to dig into this a bit more in a separate post, but I think this effect is part of the reason why gourmands are so popular right now. A perfume that smells like vanilla candy and says that it smells like vanilla candy right on the bottle is easy to describe literally, which is comfortable for people who need unambiguous interpretation to enjoy an artistic or aesthetic experience. It’s easy to understand and describe a vanilla cupcake gourmand in a way that it is not for, say, a complex aldehydic floral. Chanel No. 5, for example, is classified as a floral perfume but it doesn’t smell like a bouquet of flowers. Its olfactory objective isn’t to smell like a composite of the individual floral notes that are described in its marketing.

The elusive nature of describing scent can be a playground for expression—it is an invitation to lean into the incomprehensible in a world that demands everything be comprehensible. Maybe you want to approach fragrance from a more emotional place. Many fragrances elicit some sort of emotional response, and approaching the boundaries of expression and critique using that response as a starting point can be more interesting than straightforward description. Treating quotidian scents as subjects of critique can alleviate the impulse to rely on literalism when it comes to describing fragrance, freeing you from the confines of notes and categories (though, again, they have their place when it comes to contextualizing perfume).

Some Examples of Expressive Fragrance Writing

One of my favorite fragrance writers is Kashina, whose work is collected in several volumes published by Antifurniture, including her recent release Messages from a Dark Room. Her ongoing scent journal is also available through her Instagram account. Kashina’s writing tends towards the figurative and imagistic, full of personal associations, poetics, and observations. She writes equally evocatively about perfume and scents she encounters in nature:

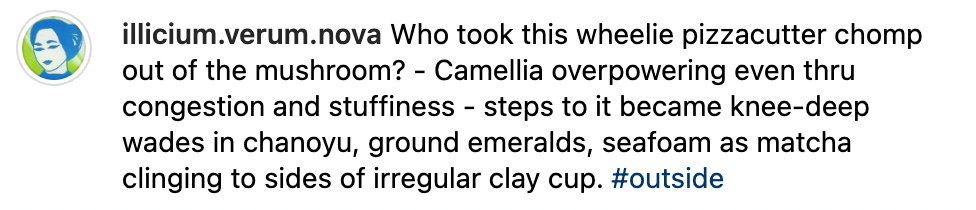

The Instagram account @itsmellscrazyinhere is primarily regarded as an avenue for entertainment of the “gawking and staring” type, but it often reveals a higher truth about a fragrance than any literal description of its notes as dictated by a marketing department can. Many of these “unhinged” musings are quite expressive, narratively-rich, even poetic:

If poetics and weird narratives aren’t your thing, I recommend checking out Audrey Robinovitz/@foldyrhands—another favorite fragrance writer of mine. Audrey’s reviews go into deep dive reviews that are often full of allusions to history, literature, and philosophy, demonstrating how we can contextualize the olfactory within other disciplines:

Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Haloscope, https://www.haloscope.org/post/beyond-the-pleasure-principle

Approach commercial fragrance with an exploratory mindset

These fundamentals to cultivating an appreciation for the olfactory should keep you going for a good long while, perhaps even forever! But maybe you’re like, “Quinn, I didn’t ask you about how to get into fragrance so I could hear some hippie dippy bullshit about smelling a pineapple or whatever, tell me about PERFUME!”

Even if you want to get into Fragrance with a capital F so you too can become a perfume snob, the process is still basically the same: smell everything you can get your hands on and be thoughtful about it.

Here’s some advice for aspiring fragheads specifically:

Go to places where you can smell lots of fragrances in one spot

For most people, this will probably entail a visit to a department store, Sephora, or Ulta. If you’re lucky you might live in a city with an independently-owned perfume store as well.

On the plus side, most places have bottles out on display so anyone can browse and sniff at their leisure, which is much less stressful than having to ask a sales associate to spray every fragrance you want to try. However, a good sales associate can be helpful if you want a little guidance. The maxim used to be that the sales people at the perfume counter often were not interested in perfume themselves and only really knew the points of the sales pitch they were supposed to give customers rather than any general knowledge about perfume, but I find that is less true nowadays. (One humorous exception: I recently went into a fragrance shop at the mall near where I work and when the sales associate asked me what kind of scents I like I told her that I like vintage-smelling, classic fragrances and she immediately suggested Black Opium lol).

I usually don’t feel like talking to anyone so I try my best to seem as unapproachable as possible if I can be left to my own devices at a store (obviously this isn’t an option in a counter service situation). Since our goal here is exposure and surveying the olfactive landscape rather than finding one specific fragrance to buy, you don’t really need a plan of attack, you can just start sniffing. However, if you are the type of person who is easily overwhelmed or likes to undertake new experiences methodically, here are a couple different approaches you can take:

One approach: start at a department store and smell all the classics you can get your hands on. You might have a few names in your head just from ambient exposure: Chanel No. 5, Guerlain Shalimar, Mugler Angel, etc. You can save a list of classic fragrances ahead of your visit if you want something to ground your exploration in. A lot of classic/vintage fragrances might smell very similar or the same to you at first, with repeated exposure over time you’ll notice differences between them, sort of like how you need to try multiple wines or craft beers before they start to differentiate on your palate. It can be a fun challenge to pick out the differences between similar fragrances.

Another approach, one which requires talking to people: again, start at a department store. Ask the sales associates at each of the little branded fragrance kiosks if you can smell the brand’s oldest fragrance, their newest fragrance, and their most popular fragrance. This will hopefully give you an idea of the range within a brand so you can determine if you want to explore it more fully and expose you to lots of different brands without getting too overwhelmed trying to smell every single offering.

One more approach: pick a particular note or type of fragrance that you are interested in, say, “rose” or “woody” and head over to the fragrance store of your choice. Smell all the fragrances you can find that match your chosen criteria. Sephora has little labels by all their fragrances that give them a basic categorization which can help guide you. If there isn’t any signage describing fragrance notes at the store of your choice (or other obvious indicators like the word “rose” in the name of the fragrance), this is another instance where a sales associate can be of help. This approach is especially helpful if you want to learn to recognize how smells from your environment have been interpreted through perfumery.

Sephora used to be great for surveying perfume and had plenty of classics that would be of interest to a newcomer. They still have some of the stalwarts, but now their fragrance department has mostly been taken over by venture capital-backed faux niche influencer slop that I frankly don’t find very interesting or illuminating. And they don’t even give you free samples anymore. Maybe you’ll love ‘em but if I were you I would focus on the classics first.

Whatever your approach and wherever you start sniffing, remember to bring a pen with you so you can label your blotters and remember what they are when you smell them later. Fragrances often smell very different in a store vs. in the open air simply because a store is loaded with competing aromachemicals bouncing around interfering with your sense of smell. This is more apparent in smaller stores than larger ones, but it happens anytime you have a ton of people all spraying perfume at the same time in the same place. Even if you don’t want to keep your favorite blotters for long, at least bring them outside so you can smell them in fresh air. I think you should keep your blotters until they completely dry out so you can experience the full spectrum of a fragrance from its opening through the drydown to its base. Whenever I’m sampling a bunch of fragrances in a store I just throw all the blotters in my bag, which can muddle them a bit but they’re usually fine when I get home and separate them. You can also bring glassine envelopes with you so you can separate your blotters and prevent them from contaminating each other. This will also slow down the drying process, allowing you to revisit a scent for much longer than you would otherwise be able to.

Smelling new fragrances is fun, but make sure to revisit scents you’ve previously smelled. As you become more immersed in fragrance your tastes will change over time. Write down observations about what you’ve smelled and review them later with a fresh nose. Over time you’ll find you have more to add. Draw connections between the smells in your environment and those in the perfume aisle. Note: it’s just as important to learn what you don’t like as it is what you do. This is how you cultivate taste and, as described above, smelling unpleasant things can be just as evocative and interesting as smelling pleasant scents. This notion applies to commercial perfumery just as much as it does to environmental smells.

Go Forth and Smell

My point here is that appreciating your sense of smell opens up a whole new way of experiencing the world, creating a new avenue to interact with it in a way that is distinct from the visual, auditory, and tactile. However you decide to engage with it, in whatever degree, encountering and contemplating the olfactory will enrich and enhance your life.

Note: I think the author is missing some words—redolent, for instance, is historically a smell-exclusive adjective.

This!! "exemplifies the cultural moment we live in where an unambiguous explanation of any particular work of art is considered a requirement to appreciating it—if art cannot be fully exculpated it is considered 'bad'"

What a great piece, Quinn <3

loved this article sm! such a necessary and often overlooked topic - ty for the shoutout! 💖